I Don't Need To Protect My Favorite Shows

I think Emily Asher-Perrin is the best blogger on Tor.com right now, and she wrote an article called It’s Time To Get Over Firefly. Which basically states that Firefly is overrated because a) it ended before it had a chance to disappoint us, and b) some of the impending plotlines and themes were a little troubling (specifically, the overarching themes of Southern Restoration and the appropriation of Asian themes without actual Asian people).

This caused a hubbub in certain circles. “How dare she say Firefly is overrated!” people cried, rallying the flags, and I’m all like What, hey, why?

I don’t get that defensiveness over fandom. I never have.

I love old-school Doctor Who. But the episodes are padded, the special effects are laughable, and the acting is often wooden. So what? I can acknowledge those flaws and not have them bother me. If I waited for a show to be perfect on every level before I could enjoy it, then I’d never watch a damn thing.

And even if I thought the acting on old-school Who was wonderful, hey, it’s a big world. Some people think Daniel Day-Lewis, the most acclaimed thespian of our generation, is a terrible actor.

Am I such a neurotic that I cannot enjoy something until everyone loves it in the way I do?

And I see all these silly fandom scuffles where people get really bent out of shape because You Do Not Understand The True Batman or ZOMG How Can You Not Love Star Wars and You Dumbass Picard Is Way Better Than Kirk, and some people are getting seriously upset over these things – as though they cannot rest until everyone shares their opinions. As though somehow, a difference in taste is a wound to their very soul.

And I think what happens is that people are making the silly error that “I love it” means “It is perfect.” This is a thought process that inevitably leads to ruin, whether it’s in fandom or work or in romance. Something can sweep you up in whirls of dizzying rapture, but it’s not that it doesn’t have flaws – it’s that you don’t mind them. (Usually because the good stuff is so damned good that you may not even notice the fractures in the background.)

Look, I get that this TV show or movie or comic book has spoken to something deep within you. It expressed something important about your very nature in a way that you wished you’d been able to do it, becoming in a very real sense a part of you. And that’s great. That’s the power of fiction.

But then people make the leap of, “Well, if I like it, then everyone should!”, turning their love into a popularity contest, acting as if they can make this show as well-loved as possible then somehow they’ve vindicated something about themselves. And their fandom mutates away from expressing a love for the show and into a sort of baffled belligerence that anyone could ever not like this thing so crucial to them.

Then they do the usual thing zealots do – they get angry whenever anyone points out an error with the thing they love, they take it personally, and they try to stomp that opposition to the curb so no one brings up this troubling issue ever again. It ceases to be a fandom and more like a religion, where the One Truth Faith must prove itself over the bodies of others.

Look. Pointing out flaws shouldn’t destroy your enjoyment. Poke deeply at the greatest works of art in the world, and you’ll find so-called flaws. Those flaws bother some people, don’t bother others. They don’t bother you, apparently, and that’s all that should matter. Love shouldn’t consist of a battle to the death to justify its existence – there will always be people who don’t like what you do. There will always be people who don’t believe as you do. And as long as they’re not trying to cancel your show (hint: pretty much no fan is ever trying to cancel your show, and none successfully), then their difference of opinion shouldn’t matter.

Relax. Sit back. Let all of those other people roll on with their hatred. The glory of the Internet is that you can find people who like what you do, and fandom should be about accentuating and deepening that like instead of angrily justifying what you enjoy to people who wouldn’t like it anyway.

It’s a big world. Big enough you can sit back in your living room and read the words of people who agree with you. And on those occasions you find someone who disagrees violently, it’s okay to clear your browser cache and move the fuck on.

The Bees Are Back In Town

Who is the most popular character on my blog? If you think it’s me, you’re wrong.

Gini? Nope.

Basing popularity on “How often people ask about them,” the most popular person on this blog is… my bees.

And I have good news! Watch this video!

That’s right – the bees survived the winter. Which was a very uncertain thing for a while. We saw the bees doing cleansing flights a while back (bees do not poop all winter, instead waiting for spring to do their business outside the hive), but then we had several cold snaps again in March and didn’t see them for a month. It was entirely possible that the bees had died in that chilly final stretch, which included four inches of wet snow on the final weekend in March.

Ah, Cleveland. We love your weather.

Better yet, we know the queen survived, because these were new bees. How can you tell? Well, younger bees do an “orientation flight” around the front of the hive, zigzagging back and forth as they map what home looks like before venturing forth, and the hive was alight with lots of bees making sense of the place. So the queen is inside, laying eggs – precisely what we want our queen to do.

But which bees are these? Long-term readers will know that our original bees were the Good Bees – well-tempered bees that hardly ever stung, accepting of our constant novice intrusions. The queen in that hive died off and our attempt to re-queen didn’t take, so sadly, the Good Bees all died. We replaced them with the Bad Bees – very hostile suckers who stung every time we got near them, and chased anyone who got near the hive. We didn’t feed those fuckers and they died off last winter, much to our relief.

So who are these? These are the Mystery Bees. We intended to take care of them, but we went on a trip to Hawaii in July and then Rebecca was diagnosed with brain cancer when we got back in August, so we pretty much ignored them from July on. We don’t know their temperament. Alas, thanks to crazy life-issues, we have become bee-havers, not bee-keepers (as they say scornfully at the meetings), and so we must learn to take care of these guys once we get better gloves. (The mice ate the fingertips out of our gloves.)

We’ll be doing a hive inspection once the weather warms up a bit. But it looks like we’ve got a hive in somewhat working order. That’s a bit of nice news, something we’ve been short on lately.

How To Boycott Chili's Effectively

On Saturday, I posted this half-assed bit of Twitter activism:

Not that choosing Chili’s was a wise decision anyway… RT @libco: Chili’s is Fundraising for Anti-Vaxxers http://t.co/vgRTZRkHmW

— Ferrett Steinmetz (@ferretthimself) April 5, 2014

You can go read the link if you want to find out what the hubbub was about, but basically, like many restaurants, Chili’s has various “days” where it donates some percentage of its profits to charity. The charity in question was the National Autism Association – who could be against helping Autism?

Well, I could, as it turns out, since they’re apparently notoriously anti-vaccination. (And if you’re anti-vaccination, then please. I’d tell you to educate yourself elsewhere, but if you were capable of doing the math on it, you’d have done it by now. Suffice it to say that your beliefs are doing a lot of harm to a lot of kids – and even if you were completely, 100% correct in your fears [which you are not], you’re basically saying, “I’d rather my kids die than get autism!” Which, you know, not so wonderful an approach.)

And I’m pretty sure I know how this happened: some overworked schmuck at the Chili’s HQ with a ton of work on their plate saw “National Autism Association,” said, “That sounds nice,” and approved it. That person had never had an Internet come crashing down on their head before, because usually charities to help sick people don’t come with nefarious controversies attached to them, and hadn’t done the research beyond ascertaining that they were a legitimate organization.

And so, when Chili’s reversed course, I said, “Okay, fair enough, thank you,” and undid my boycott. (Not that it was much of a boycott anyway, seeing as I haven’t eaten at Chili’s in a decade. My real boycott with Chili’s involves a lack of enthusiasm about their food.)

Now here’s the thing you have to remember about boycotts:

If you boycott someone permanently, you’re fucking up the boycott.

The whole point of a boycott is that there is forgiveness at the end – a way for these companies to get your money back. I’ve been boycotting Chick-Fil-A for over a decade now, and it’s anguish, as they’re right across the street from me and I love their food and especially their delicious breakfasts. But they’re anti-gay, and keep doing stupid anti-gay things just often enough that I’m unconvinced that I’m not hurting gay rights’ causes by filling their coffers, and so I stay away.

But if they were to do an about-face that I was comfortable with – which would, admittedly, be a high bar after years and years of disappointment – I would probably buy there more. I would reward them for doing the right thing at last, even though it took years, because when you’re dealing with something as fiduciarily-motivated as a soulless business entity, the only form of motivation they understand is dollars over the transom.

Now, I saw a handful of folks who were still fuming at Chili’s for giving money to anti-vaxxers, saying, “Well, I’ll never eat there again!” Those people are almost as dumb as the anti-vaxxers. If you yank away your money permanently, what you are teaching companies is, “The slightest mistake will cost you customers you can never get back again” – which, in this day of exceptional sensitivity and Internet-stoked fires, could be any mistake.

No. You must teach them, “You can piss us off, but you can also work to win our forgiveness.” Which encourages them to do the right thing as we define it. If you’ve dropped Mozilla because the CEO donated to Proposition 8 and now refuse to use Firefox ever again based on a single error, you’re doing it wrong.

People will screw up. You have screwed up – I guarantee this. And if all it takes for you to abandon someone forever is a single error, then you’re inflexible and punishing. Allow the companies to err just as people do – because remember, like Soylent Green, multinational corporations are made of people, and usually underpaid people trying to work under the rapid pressures of idiot bosses. Not every error is a concealed agenda, indicating that this company is committed to destroy everything you love. This is a complicated world, and things frequently get lost in the whirlwind of other concerns, and it’s frequently not obvious just how awful this is until someone with more experience looks at it.

Chili’s screwed up. They made it right, and I’m pretty sure they’ll do better vetting next time. In this imperfect world that’s all I can ask, and in this imperfect world all I can ask is that you occasionally allow a screwup to be just a “whoops.”

There is a certain grace in accepting an apology. Learn to do so, when you can.

The Only Advice You'll Ever Need To Hear About Writing. I'm Serious About This.

I had a friend who was having problems finishing stories, in part due to physical difficulties in typing and in part due to writers’ block. So when she got a chance to talk to one of her idols, arguably one of the most popular writers in America right now – a man known for being kind, wise, and generally friendly – she asked him what she should do.

He told her to not write physically, and tell her stories to people instead verbally.

She wasted a year doing that.

Did Big-Name Author give her bad advice? Yes. My friend is socially anxious, and worried about judgment already, and so for her, trying to tell stories to people led to a year of paralytic silence.

Was Big-Name Author wrong to give her advice? No. But what we experienced writers often forget to tell novice writers is that writing advice is not generic.

A muse is a very finicky creature – not quite a pet, but more like a wild animal you must tempt to your doorstep via a series of elaborate machinations. And each is different. I have a very businesslike muse clad in a three-piece suit, a great suited moose muse possessed of a Protestant Work Ethic, who shows up the more I show up. And so I write every day. But I have friends who have much more hedonistic muses, sinewy muses who arrive only after they’ve spent a weekend drinking wine in the company of good friends, and so they write well only when they’re in a fine mood.

Learning how to attract our muses changes our lives, if we’re serious about writing. I make time every day to write, which isn’t easy when I have a godchild with a terminal illness – but if I don’t, my stories don’t flow. My friends with the hedonist-muses have to structure their lives to have wonderful parties and friends staying over, so their environment encourages their muse to show up more.

If you’re lucky, your muse is very like your Hero Author’s muse, and you put the tin of cat food out on the porch and the stray-cat muse shows up! But if you’re unlucky, you put the tin of cat food on the porch, and you’re inside waiting for the cat to arrive while there’s a flouncy dog-muse in the back yard waiting for you to show up with a ball.

And if you’re unlucky and inexperienced, you may keep putting the cat food out on the porch for a year, thinking all muses are identical.

Now, when I say “muse,” that’s a little artsy-fartsy for me (and of course it is, as my stodgy Business Moose muse wants charts and graphs), but the point is that every writer has their own unique process by which they produce good material, and they stumble upon those processes by continual experimentation. Some writers need to do twenty redrafts, others smudge up their manuscripts and make them worse by overthinking solutions. Some writers must plot to get things right, others do better making up the ending as they go along. Some writers need critique groups, others need only their own feedback.

Your goal as a writer – your only goal, really – is to find out what gets you producing your best stories.

And your muse’s comfort often comes at the expense of your own. I mean, I’d love to be a get-it-done-in-one-draft kinda guy, but experience has shown that four to six drafts is what gets me publishable – and so I have to do the ugly work of hard revision. I’d love to work in isolation, but I need three or four people poking at all my weak points because I can’t see them in my own fiction. I’d love to think of character interactions in terms of “petitioner” and “granter” so I could raise tension in my fiction, but when I’m in the moment I just see two people and forget about hidden agendas. I wish I could write a story in one sitting, but I need to contemplate each sentence carefully even if I’m going to throw half of them away in redrafting.

I’m not efficient. But I get there.

Getting there is all that matters.

Each writer’s path is quirky and weird, because creativity is quirky and weird. And when you hear some writer saying the things you have to do, what they’re doing is saying, “Here’s how I access my muse. She hides from me otherwise. If your muse is similar, then this will call her. And if not, well, bring the cat food in and try another way.”

I got some advice from that same Big-Name Writer. He told me I needed to buckle down and forget the short stories, write novels. I ignored him, and wrote stories, because that felt right to me. And lo, following my inner muse turned out to lead to Great Improvement for me. But only because I was lucky and wise enough to say, “Big-Name Writer, I love you, but that’s not gonna work.”

Keep your ears open, because other Big-Name Writers (and small ones!) will mention techniques that do work for you. But your only goal as a writer is to find whatever crazy actions get you completing and improving stories. If you find something that’s stopping you from making good work, then shrug it aside no matter who told you.

That’s it.

Now go find better ways to court your muse.

This Is The Best Commercial Ever. A Serious, Actual Commercial.

It is not a prank, or a comedy sketch. This is an actual commercial done by 10:10, a British environmental group whose intentions are outlined in this Cracked article on PR disasters.

But I shan’t spoil it. Just watch.

On Fort Hood

People come read essays for nice summaries, where they map out easy Buzzfeed-friendly solutions: How could we have avoided this tragedy? This simple solution will show you how!

And my honest answer is, “I don’t know.”

My initial gut reaction is to say that we need to get the soldiers more help, prioritize funding to veteran care. But that’s because there are a lot of depressed veterans out there shooting themselves in the head, and I think they could use the help. A guy who’s so far gone he feels like shooting people at random?

I don’t know what causes that.

I don’t even know if there’s a common cause. Maybe the last shooter was crazy in an entirely different way.

And I think what a lot of people are doing now is taking their generic solutions for “Here’s how we make things a better world” and slapping them onto this repeated tragedy because heck, anything is better than doing nothing – so we’ve got guys saying we need soldiers to have easier access to guns on base, or less access to guns, or to change the way the media reports on these shootings, or to change the regulations on psychiatric evaluations or whatever else they’ve been pushing for all along….

…but me? I’ll admit that this is completely outside my element. I talk about writing and gaming and relationships, because I know a lot of writers and gamers and people who date. I have yet, thank God, to even meet anyone so disturbed as to go on a shooting spree, let alone know enough of them intimately enough to start drawing conclusions about their lives.

And I think more funding to help our veterans couldn’t hurt, as I think maybe the feeling of isolation by soldiers hurts them, that sense that we’ve sent them to hell and then abandoned them. But would that have prevented this shooting? Or any other?

I don’t know.

I just don’t know.

On Common Core Math

My Facebook page has been alight with anger over the concept of “Common Core” math – the new way we’re teaching math to young children. They’ve posted pictures of Common Core examples, decrying their complexity, the stupidness of needing a new method when the old methods we had worked just fine, and how dare teaches do this stupid thing.

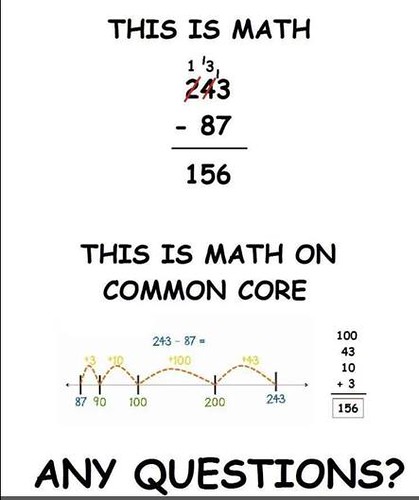

One of the most common ones I’ve seen going around is this:

Yeah. My question is, do you realize how fucking hard the concept of “borrowing” is to someone who’s unfamiliar with math?

What I’m seeing here is a twofold storm of ignorance and fear:

1) Explaining things to newbies is entirely different from explaining things to experienced people.

Look, I sell Magic: the Gathering cards for a living – a complicated card game with a ton of rules. And time after time, I’ve seen experienced players try to teach newbies how to play the game…

…and they often confuse the newbies so much that they alienate them.

The problem is, the experienced players have been slinging cards for so long that they’ve forgotten how hard this game was in the first place. So when they teach, they tend to concentrate on the things that players who are bad at the game need to know – which is an entirely different thing than what players who are totally unfamiliar with the game need to know.

So they rush past the core concepts of the game – the base mechanics that they’ve internalized so thoroughly that they don’t even think about them any more – to focus on things that make no sense if you don’t get those fundamentals. I’ve heard them casually saying things like, “Okay, you gotta remember to play instants at the last minute, and leave your mana untapped until you need it” to baffled people who barely understand which card is which.

It’s a testament to how much fun Magic is that thousands of people still play it, despite these substandard introductions. But Wizards of the Coast, being a smart company, recognizes that the #1 barrier to entry for Magic is overcomplexity, and so periodically creates products that are newbie-friendly. And those novice-aimed products are often scorned by the “experienced” Magic community as being too simple, too stupid, too strategy-free.

“I learned it the old way!” they cry. “And I still understood!” Forgetting entirely that a) it took them a lot more effort to ingest that knowledge than they remember now that it’s reflexive, and b) a lot of people didn’t learn it, and walked away, and if the goal is to get as many people playing Magic as possible then maybe ignoring the failures isn’t your best idea.

Likewise, this Common Core example isn’t a fair example. Yes, there are fewer steps in the upper diagram – but conceptually, sorting each number into neat rows stacked on top of each other, and knowing that you can borrow a number, and understanding that the borrows cascade, and remembering the edge cases, are actually pretty hard to get for many kids. I know I struggled with it. There’s a ton of buried complexity in this, and I’m pretty sure if you showed this same thing to two people unfamiliar with large subtraction problems, the more visual example below might work better.

Plus, the Common Core example below is a better way of conceptually explaining things. Yes, kids can learn the rote method of “stack and subtract,” but that doesn’t actually teach them to internalize how math works. When I’m looking to figure out what the difference is between a dollar and 97 cents, I don’t mentally place a 100 on top of a 97 and go through it column-by-column – I count forwards from the lesser number until I hit 100.

It could be argued that in fact, the old beloved style actually presents a barrier to conceptualizing math, sort of like teaching kids that the letters S-I-N-K mean “sink.” It’d work. It’d get them to recognize what a phone is. But without presenting all the complicated phonetics behind it, getting them to spell out each letter, they’d probably not really understand the concept of words – they’d understand that a few grouped letters mean a handful of things, but not be able to extrapolate that to dope out new and unfamiliar words.

And even aside from that, from what I am told the Common Core doesn’t replace the old method, it supplements it. Here is where I venture into the unfamiliar waters of “people said,” but from what I’m led to believe the old method is still taught in class – it’s now just one arrow in a quiver full of approaches to help gets learn to add big numbers. If someone happens to find the columnar method more intuitive, they can use that in their heads. It’s whatever sticks.

Which brings me to point #2:

2) Parents are fucking terrified of looking stupid in front of their children, and hate to actually do homework. Again, here I venture into theory, but I think much of the backlash against Common Core stems from the fact that a lot of parents get off on being the all-knowing wise folk, and looking dumb in front of their kids robs them of a special power. Having to sit down with their kid and go “I don’t know how to do this” makes them feel like the schools are somehow showing them up.

And then they find themselves back in grade school, forced to understand a new concept. They’re not just helping their kid with homework; they’re back in grade school doing homework, and grah I learned what I need to I shouldn’t have to work to internalize some new approach what I knew worked fine. And rather than acknowledging that discomfort of this is something I don’t know, they instead freak the fuck out about how ridiculously hard this all is and it’s difficult and won’t someone think of the children?

But those someones are thinking of the children. If it’s hard for you, remember back to those early days when everything was hard for you. Regardless of whether you use the upper old version or the bottom new version, your kid is going to struggle to import these new ideas into their head – and bitching about the approach because you don’t get it seems small, anti-education, and churlish.

And hey, maybe your kid is finding Common Core too complex. Maybe that’s because for her, the upper example is more intuitive. But I wonder how much of that struggle stems from the fact that Mommy and Daddy are expressing obvious frustration with it, bitching I don’t know why they do this, and sending the signal to your kid that this is actually a dumb way to approach it. They pick up on things like that, kids.

So my take? Is that yeah, it’s more work for you, but as a parent, your job isn’t to make your life easy. It’s to do what’s best for your kids. And if that means you have to go back to grade school again and start over, well, go back and sit down next to your kid in class and learn along with them.

Teach them that everyone feels dumb from time to time. That even Mommy and Daddy never stop learning new things, and that new things are exciting. Because honestly, that’s a way better lesson they’ll learn than anything they can get in school anyway.

EDIT: I’ve had a lot of people saying, “I don’t like it when my kid switches schools and has to learn Common Core under the assumption that he’s been taught it all his life,” or “I don’t like Common Core because my kid can already subtract the old way and they’re punishing her for not knowing this new method,” or even “I don’t like it because the schools don’t give me any warning or context and now I have to train my kid with no help.”

In that case, you are not actually complaining about Common Core. You are complaining about an inflexible educational system that is utilizing Common Core improperly. Note how your complaint is not actually that Common Core is too hard, recognize that this essay is chastising those who criticize Common Core because it is too hard, then take your valid concerns about a one-size-fits all educational approach and move on. This was not meant for you.